|

Plaster is a medium of reproduction, of the solidified, dried-out state. Goethe called the material "chalky and dead" when viewing his cast of the Medusa Rondanini, a portrayal of that mythological figure whose horror lies in her deadly, transmutative ability to turn flesh into stone.

Plaster is also—alongside photography—the medium of classical archeology, an instrument archaeologists have used and still use for all manner of things but in particular to understand Greek and Roman sculptural forms and subsequently to reconstruct them. Translating these into the seemingly characterless material brings about a reduction that helps significantly in formal analysis; and correlatively, plaster casts of ancient sculptures are also depicted photographically in archaeological specialist literature—devoid of color and lacking in structure (Fig. 1).1 What is ostensibly depicted in plaster casts is actually never present and remains ultimately invisible: the original to be reconstructed. As schools of comparative observation of and knowledge about sculpture, archeological collections of casts (Gypsotheques) have served until now for educating students and research into ancient sculpture. Traditional holdings—consisting mainly of casts of sculptures in noble and papal collections in Rome and Florence—are expanded in these modern collections of casts, such as the Skulpturhalle Basel, and grow at an anachronistically slow pace. A collection assembled for archaeological research encompasses replicas of Greek and Roman sculptures from the Archaic period to late antiquity, and architectural sculptures and relief plates of the most important ancient architectural structures from the Parthenon to the Pergamon Altar, to Roman triumphal arches.

But the history of plaster casts is not as clear and straightforward as it may initially appear.2 Their complexity has its origin—at least in part—in the material as well. Although a rapidly decaying material requiring protection from weather and moisture and difficult to repair, the casts evince, in contrast to the famous sculptures they replicate, a latent immortality that rests solely on the integrity of the casting molds from which they were created. In this respect, Goethe’s chalky and dead aesthetic assessment of the material asks to be taken to an even greater extreme: the casts were only ever un-dead: zombie-like reproductions of art from the past that can be resuscitated from their forms at any time even if an arm or leg is missing. In this and the plaster casts’ therefore associated ease of mobility—with Aby Warburg one could speak of "Bilderfahrzeuge" ("image vehicles")—lies their historical resilience since antiquity and also the reason why it is possible to speak of the histories of linkages between art and artists, science and scholars in connection with their appearance.

Amin El Dib photographed plaster casts at the Skulpturhalle Basel, a collection of great importance for twentieth-century archeology.3 It is relatively unusual for a contemporary artist to access a collection of plaster casts—in order to make art. Today one is more inclined to shy away from overly explicit references to the various classical heritages of old Europe.4 The at times slightly dusty casts of antique sculptures in university collections are often used as backdrops for contemporary art exhibitions, but are themselves rarely extolled as artistic objects any more. In this lies, alongside their prestige value for particular noble owners, an essential motive for the establishment of Gypsotheques. Since the second half of the eighteenth century, an increasingly concentrated network of plaster-cast collections provided generations of academy students and archaeologists with the opportunity to study the most famous ancient sculptures from Roman and Florentine collections that were venerated over centuries via their association to the best connoisseurs and artists. The final point of reference behind the Roman sculptures, which in some cases bore the signatures of artists with Greek names, was classical Hellas. This was virtually unattainable in the Ottoman Empire; Greek art of the fifth and fourth centuries BC, however, was considered the highest ideal based on the writings of ancient authors from the Roman Empire (Pliny the Elder, Pausanias) and the aesthetic philosophy of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–68). To a certain extent the association to Winckelmann and Michelangelo was inherent to the statues at the Cortile del Belvedere. The ultra-academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme sought to make the viewer aware of this (Fig. 2): the greatest sculptor, legendarily blind in his old age, approaches—his hands led by an ephebe-esque student in an exemplary contrapposto—the Torso, the work of ancient sculpture he had professed to admire since his youth, which Gérôme then enlarged to a colossal scale. The painting plays with the imaginative world of the nineteenth century, in which this close relationship, charged with homoerotic desire, reached an emotional peak, which also had a point of origin in Winckelmann’s wistful descriptions, such as those "of the famous torso in the Belvedere…, which is generally called the Torso of Michelangelo because this work was especially highly regarded by Michelangelo, and he made many studies of it."5 Prior to concluding his enthusiastic manifesto on classicistic beauty, Winckelmann stands despondent before the torso and bemoans—despite the previously executed, prescient addition of the missing limbs—its mutilated state: "I finally understand the beauty of this Hercules, only to weep for the irreparable damage it has sustained. Art weeps with me." Indeed Winckelmann’s rousing empathizing with the ancient masterpiece ultimately aims to reverse the ideal of ancient sculpture, whose beauty is supposed to educate people (and conduct them toward moral paths). This ideal haunts exemplary academic behavior and lives on even today in the forests of cast-plaster statues in educational collections and may (unknowingly) frighten off many a visitor.

Winckelmann’s eloquent yearning for antiquity infected an entire generation in France and Germany, but marble statues were rarely experienced in person on Italian soil.6 The non-privileged majority still had to be content with drawings and engravings because even life-size casts based on originals were rare and not accessible to everyone until the advent of plaster-cast collections in the 1760s for the purpose of educating the general public. Italian noble families had jealously guarded their ancient antiquities for centuries; the making of casts was authorized only after significant diplomatic and financial efforts. In Germany, the royal collection in Düsseldorf was one of these prestigious exceptions: here Prince Johann Wilhelm, who was married to Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici and therefore extremely well connected in Italy, was able to amass an extensive collection of casts at the beginning of the eighteenth century.7 These comprised the core of the Mannheim Antikensaal collection in 1767 and have had a significant impact on the public since then. Goethe saw the collection as early as 1769: "Here I now stood, open to the most wonderful impressions, in a spacious, four-cornered, and with its extraordinary height, almost cubical saloon, in a space well lighted from above by the window under the cornice; with the noblest statues of antiquity, not only ranged along the walls, but also set up with one another over the whole area; —a forest of statues, through which one was forced to wind; a great ideal popular assembly, through which one was forced to press. All these noble figures could, by opening and closing the curtains, be placed in the most advantageous light, and besides this, they were movable on their pedestals, and could be turned about at pleasure."8

The French court had a large inventory of faithful replicas of Roman sculptures at an even earlier date. Francesco Primaticcio had made molds of marble sculptures in the Belvedere Courtyard at the Vatican Palace for Francis I between 1540–43, creating sumptuous bronze casts of these for decorating the Palace of Fontainebleau, which played a pivotal role in furthering the canonization of the sculptures in the Cortile. In 1666, the Académie de France was founded in Rome, placing the French court in a unique position as supplier of replicas of Roman antiquities. From then on, casts were systematically produced at the Académie and sent on to Paris for decorating—as marble and bronze replicas—the Gardens of Versailles.9 A century and a half later, the originals arrived at the Seine: Napoleon’s raid seized Rome’s most important antiquities—including the Laocoon Group—in the name of freedom and brought them to the Louvre Palace, since 1793 the Musée Central des Arts de la République, where they were publicly accessible.10 Fifteen years later, following the Congress of Vienna, most of the works were returned, but the impact of their long-term presence in Paris was enormous: the founding of the Atelier de Moulage for the casting of Roman antiquities became the model for large-scale, plaster-replica foundries, such as the Königlich Preußische Gipsgussanstalt [Royal Prussian Plaster Casting Facility], founded in 1819 in Berlin.11

Even further away than the Italian antiquities were the originals from classical Greece: it would be some time until museums that would exhibit them were established in the German-speaking world. To a greater degree this was initially the case in Munich with the pediment sculptures from the Temple of Aphaea on the Greek island of Aegina, which Ludwig I had acquired in 1813. The marble works featuring abundant traces of preserved coloration were exhibited at the Glyptothek that opened in 1830. The pediment sculptures, however, caught between archaic and classical styles, did not yet meet the classicist expectations of the public, even though the art-historical significance of the ensemble relative to Winckelmann’s "History of the Art of Antiquity" was embedded in the exhibition concept from the very outset. To some extent, the emotional rejection is itself apparent in the masterful restorations created in the studio of the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen in Rome between 1813 and 1815. Evidently, Thorvaldsen and his workers were unable to achieve the same peculiar expressive severity in replicating the original faces.12 No comparison can be made, however, to the initially tepid but ultimately enormously positive response that the arrival of the Parthenon Sculptures in England generated. Exhibited for the first time in 1807, they were purchased by the British Museum in 1816. Within a few years, casts of the pediment figures and friezes reached European collections. The power of the High Classical sculptures, known previously from drawings to only a few, began to develop and compete with the special position of the Roman sculptural canon. Antonio Canova respectfully refused to restore them, thus situating himself within a tradition similar to the narrative told about Michelangelo and the Belvedere Torso.

It must be noted that during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries plaster casts (at least in the German-speaking world) were the only way for most people to get a true—that is, life-size and three-dimensional—view of the virtually inaccessible originals, which Winckelmann had described in the 1750s and ‘60s. While the widely known, monumental female head (Juno Ludovisi) at Goethe’s house in Weimar was not only viewed by its owner as a stand-alone work of art and presented as such, in addition to providing a lasting testament to Goethe’s life in Rome thirty-five years earlier, to a certain extent the casts also signified—alongside the few marble originals in the courtly and noble collections of Germany—a compensation for the very lack of genuine exposure to antiquity. Goethe, however, had already been living in Rome then, in the apartment on the Corso, amongst his casts.13 After moving within the same building, he describes his newly reconfigured apartment:

"This new lodging of mine now invited us to dispose in congenial order and favourable light, a number of gypsum casts which had by degrees been gathered about us; and now, for the first time, did we properly enjoy a highly valuable possession. In Rome, where one is constantly surrounded by the plastic art-works of the ancients, he feels as in the presence of Nature, encompassed round by the Infinite, the Unsearchable. The impression of the Sublime, the Beautiful, however beneficial it may be, disturbs us; we yearn to invest our feelings, our thoughts, in words. For this, however, knowledge, insight, comprehension, are necessary. We begin to detach, to distinguish, to arrange, and this, too, we find, if not impossible, yet in the highest degree difficult. We therefore at last fall back on contemplation, which is all admiration and enjoyment.

…When in Rome you become habituated to the daily enjoyment of the representatives of that hale old world, you grow eager for constant uninterrupted walk and conversation with them. You desire to have those forms always beside you, and good gypsum casts, as the most characteristic facsimiles, offer the best means. You open your eyes in the morning and feel the most excellent influences affecting you. All your thought, all your feeling is accompanied by such forms; it becomes utterly impossible to sink back into barbarism. The first rank in our estimation was held by Juno Ludovisi, who was all the more prized and reverenced by us that the original was only seldom, and by good chance, to be seen, as we could not but deem it a signal happiness to have it always before our eyes; for none of our contemporaries, on his seeing it for the first time, dared assert that he was equal to the sight."14

Contained in this relatively inconspicuous passage on his plaster casts in Rome are quite a number of Goethe’s primary themes concerning his conception of art: the insistence on educating oneself on antiquity, whose sublime and unfathomable beauty is equated to the beauty of nature; the heightened intimacy of the close relationship—on the edge of the bed—that only plaster casts can afford; the belief that surrounding oneself physically with ancient art would close the door on barbarism forever ...

The latter was, of course, thoroughly contradicted by the sinister art processions of the Nazis, in which the discus thrower Lancelotti, acquired from Rome, was carted through the city center of Munich to the Glyptothek in 1938.15

Thus, the plaster casts are in many ways about the continuity of the "presence" of contacts, also in a purely literal sense. However, this contact is never direct, but broken medially—at times in multiple ways. And here a closer consideration could be made of what one actually desired (and desires) to see on the surface of the plaster casts because their lusterless pallor is perfectly suited for projections.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, Italian formatori traveled across Germany, plaster cast makers who carried in their baggage the casting molds that they had always made—or thus they wanted to make their customers believe—directly from Rome’s hardly accessible antiquities, not from already existing, easier, and cheaper available copies.16 Thus, the Göttingen archaeologist Christian Gottlob Heyne still expressed doubts in 1774 that the related assertion of the Ferrari brothers—who were traveling through Germany at the time as formatori—was always true.17 Proving this was usually not feasible, however, since there were still no comparable casts of originals in nearby collections, which could have acted as reference works for successful copies from marble originals. But from 1773 onwards, the antiquities collection in Dresden presented such an opportunity. Based on casts made by the Leipzig art dealer Carl Christian Heinrich Rost, it was soon revealed how mediocre the quality of the traveling forms often was.18

The quality of a cast is measured—of course—according to its faithfulness; the negative form of the mold bears the reference of the reproduction to the original. This is likely due to the predominant notion of the artist’s idea in early eighteenth-century classicism that the "auratic" character of the originals was not lost when moving through this referential framework. And perhaps dealers—apart from pragmatic-economic motives—emphasized the affinity of the casts to their originals so extensively precisely because in the process of copying no real physical contact occurred; the mold forms were always the separating intermediary link.

But when we talk about "templates" and "originals," it cannot be ignored that the situation is even more complex. After all, as mentioned, the traditional casts are replicas of the most famous works in Italian and papal collections, ancient Roman marble sculptures. But these too are for the most part nothing more than antique replicas—based on casts of Greek originals in bronze. The consequence of Rome’s conquest of the Greek world in the second century BC was the infiltration of the ideals of Hellenistic (luxury) culture into Roman aristocracy. On the Gulf of Naples, Roman millionaires competed to build the most unusual villas; their gardens and atria were filled with masterpieces of Greek art. Access to highly revered bronze originals from plundered Greek cities was only possible for the absolute pinnacle of Roman aristocracy; the rest procured the precious marble replicas. An independent art industry arose in the Greek east of the empire, from where artists’ workshops specializing in replicas of the opera nobilia also immigrated to Rome and Naples, supplying ancient art to Roman high society and the public spaces of the cities in the empire. Without this enormous cultural transfer (on a material level in particular from bronze to marble), archaeologists would know next to nothing about Greek sculpture. Winckelmann would probably not have gone to Rome in search of classical art and almost half a century later Lord Elgin would have hardly had the idea of bringing the Parthenon sculptures from Athens to London.

Both archetypes and the origins of the cast collections must therefore be attributed to the ancient Roman replica workshops. They produced the widely divergent lines continued at the Basel Skulpturhalle and in the photographs of Amin El Dib. Damages arising from the Roman obsession for incessantly copying Greek masterpieces, however, primarily affected the sculptures themselves. Here the Greek author Lucian (second century AD) gives voice to a lamenting of the replica status of a bronze of Hermes at the Athenian state market:

"Jupiter:

"... But who is that brazen man, that is running up to us in such haste, of so fine a shape and so perfect in all his contours, and wearing his hair tied up after the old fashion? Really, Mercury, it is your brother, who stands on the market near the [portico named] Pœzile; I perceive it by the quantity of pitch, with which he is bedaubed in consequence of having casts taken from him every day by the statuaries…

Hermogoras:

Just as our statue-founders

Had me under hands; as they bepitched me

On the breast and back; and a ridiculous corset,

With apish art were melting on my form entire,

Like a seal impressed in wax;19

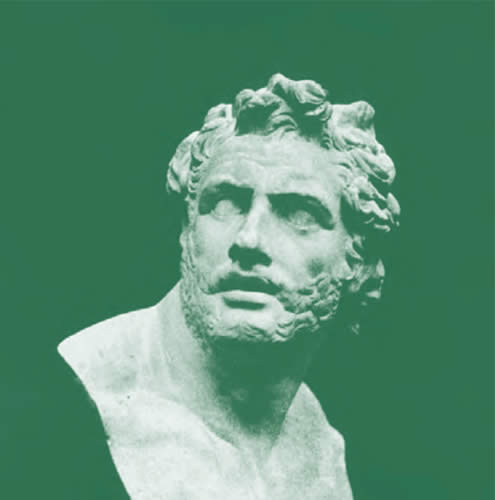

When 430 plaster fragments of models from this type of replica workshop from the first-century A.D. were discovered at Baiae in the Gulf of Naples in 1954 (Fig. 3), knowledge of this aspect of antique sculpture production was verified and expanded significantly.20 The technical process of producing the first replica began, as described by Lucian, with the production of individual forms out of plaster or bitumen (pitch), then the forms were cast into positives at the workshop, provided with an armature, and joined to the figure, which in turn then served as template for the true-to-scale marble replicas. The original, the bronze sculpture, and the marble replicas show differences according to material: fine body hair, eyelids and eyelashes, could not be faithfully executed in stone; the colorings of the marble were very different from the colorings of antique bronzes; the varying static properties of the materials made auxiliary structures, bars, and supports necessary in the case of the copies. Already at this stage—leaving the stylistic variances of the replica workshops aside—the original sculptures varied considerably from the copy. The necessary gap between the two, however, became an open space in which the copyist not only slavishly repeated what existed, but himself created something new.21 The archaeologist Christa Landwehr combined identifiable fragments with modern casts of Roman marble copies (Fig. 4). Both the precision of the copies and the variances are remarkable. Appearing on the surfaces of the ancient plaster casts are later damages along with differentiating details, which provide valuable information about the lost bronze origins. Soft plaster is more susceptible to the traces of history than brittle marble.

The fragments found in Baiae not only give us precise information about the technical processes involved in copying bronze sculptures. They are also a first-rate testament to a cultural process that was to recur in modern times with a renewed interest in ancient art of a different kind. The copyists working in Rome in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries repeated—unknowingly—the working methods of their antique colleagues. However, with one critical difference: while artists in Baiae translated Greek bronze originals into marble via the medium of plaster, these same antique marble copies were again reproduced in marble with the aid of casts. Plaster casts served as models in modern Roman ateliers and precise stone replicas were produced by means of triangulation and pointing machines.22 That the reproduction technique has its own creative potential can be measured by its influence on contemporary art. Antonio Canova embraced the working practices of Rome’s copyist workshops by beginning to make life-size plaster models in his studio—only a few yards away from the palazzo where Goethe arranged his casts.23 In a highly organized workshop set up for specific tasks, it was now possible to produce the new creations as identical (or slightly varying) marble works in series, an innovation that influenced art in many ways, on a material, conceptual, and receptive-aesthetic level. Ultimately, the relationship between the original and the copy is reversed: evident in Canova’s plaster replicas are the originals—the celebrated marble sculptures found in the museums of Europe and America are "merely" expensive copies, executed primarily by his own workers. It is astonishing that the celebrated master of the morbidezza, the perfect smoothness of the surface, took his starting point from the allegedly pallid plaster. Classical advocates of the primacy of form, in which the artist’s idea manifests itself most readily, would have seen themselves confirmed at the sight of Canova’s plaster originals. While Goethe’s consideration of his cast of the Medusa revalued the material itself—that of the original—it is based on the same relatively featureless definition of plaster: "...the charm of the marble remains not. The noble semi-transparency of the yellow stone—approaching almost to the hue of flesh—is vanished. Compared with it, the plaster of Paris has a chalky and dead look."24 As noteworthy as Goethe’s emphasis also is in its deviating from classicist consensus and seemingly anticipating nineteenth-century material aesthetics,25 one wonders whether it is not a preemptive value perception that reserves first place in this competition for the mysterious-magical marble since it is the original material (on which the signature of the artistic creative process is also found).26

A walk through Canova’s gallery of plaster sculptures in Possagno raises doubts about the devaluation of plaster—a notion popularized even today—as an inexpensive material for reproductions lacking artistically relevant material properties (Fig. 5). If anything, the effects of the plaster originals are carried over into the weightlessness and transparent softness of the marble copies. And, as with the Baiae fragments, whose surfaces bear the destructive wrath of those searching for iron and lead armatures inside the casts, history has been deposited on Canova’s plaster models in numerous layers: when a grenade hit the gallery of plaster sculptures in 1917, quite a number of the priceless sculptures were lost, the remaining were later restored at great expense.

It is no coincidence that the heyday of plaster sculptures coincides with the era of Weimar Classicism. As mentioned previously, materiality played a subordinate role in a Winckelmann-influenced aesthetic program; it was the form in which the all-dominating idea (of the archetype) was manifested.27 Devoid of structure and color, the plaster casts were thus able to act as the driving force of the ideal of white sculpture: "As white is the color which reflects the greatest number of rays of light, and consequently is the most easily perceived, a beautiful body will, accordingly, be the more beautiful the whiter it is, just as we see that all figures in gypsum, when freshly formed, strike us as larger than the statues from which they are made."28 In this respect, plaster was even superior to the brash surface aesthetics of marble and bronze.29 With Hegel, the same ideal regarding white sculpture still dominates, albeit linked to Goethe’s repudiation of plaster—in nearly the same wording—and thus in favor of the "true" material of marble: "... most directly, however, as a material, in harmony with the aims of sculpture through its soft purity, whiteness, no less than by the absence of definite color and the mildness of its sheen, and in particular possesses, by virtue of its granular texture and the soft interfusion of light which it carries, a great advantage over the chalk-like dead whiteness of gypsum, which is too bright, and easily kills with its glare the finer shadows."30 Winckelmann considered the sensitivity of the plaster casts to light as their decisive advantage; for Hegel they were too bright since the "overexposed" reproductions forfeited their inner form.

Amin El Dib takes a different route with his photographs. He emphasizes the autonomy of the plaster casts by granting them what they, according to aesthetic theory, are not supposed to possess: a unique color, a unique surface—and thus a unique history. The supposedly colorless casts give off a yellowish, orange, greenish polychrome shimmer, set against brightly colored or black backgrounds. Highlighted are not only the large fractured stone surfaces of the originals—such as the Belvedere Torso (p. ???, see Fig. 2)—but also the individual material characteristics of the plaster casts, the seams of individual casting molds, or recent damage. When viewing the photographs what occurs is precisely the opposite of the experience typically determined by the tradition of reception: the plaster grows its own skin, the ostensibly dead material is brought to life photographically. Another series by Amin El Dib, "Body and Soul" (Fig. 6), is so closely related that the images of casts and scarred body parts seem to be commenting on one other. It would be gratifying to see them exhibited together. Isolated structures take on a life of their own, bodies dissolve and flow together into new forms; photographic means are used to break up the complexity and sophistication of their surfaces, fragmenting continuities. All this attests to an exacting preoccupation with the subject, its fluid genesis. And at this point the title of the series from the Skulpturhalle is also convincing: "On the Fragility of Being".

In focusing on the inner structures of surfaces, on damage, and other traces from various time periods, Amin El Dib challenges the traditional evaluation of the material in classical art theory and art-historical archaeological science that emphasizes contours and form. On a second level, viewing the photographs from the Skulpturhalle makes one reflect on the medium of reproduction par excellence: photography and its relation to archeology.31 Newer, digital photographic methods are rapidly proving hostile towards older, "material-bound" media. In the twentieth-first century, the final domains of recording and drawing objects by hand—in historical building research and technical drawings of archaeological findings—are being replaced by fast-to-learn and time-saving photogrammetric modeling. Some detect an evil here: impressive models of complex objects suggest to the viewer a detailed level of knowledge, but this is no longer linked to the scientific image as it once was.32 In contrast to drawing, the high-resolution 3D model only attests to the processing power of the computer and the size of the underlying data, but not to the detailed on-site study of the object of research. The image no longer evidences the time spent in front of the object or the direct contact with the material. The next phase is the increasingly prevalent reproducibility of digital models. In the case of sculptural research, the end of plaster-cast-making not only appears in the form of three-dimensional computer or virtual-reality models (Fig. 7), but also—as a result of the ever-more exact and affordable technique—in the form of a plastic print: as the return of what is depicted into the real world after having been photogrammetrically reincarnated in the binary code. Thus contact with the world itself—as always in virtual reality—is finally severed in favor of the illusion.

But back to the beginning. Almost from the outset, with the availability of the first photographic processes,33 multiple lines of interconnection were drawn between archeology and photography. Sculpture was the prominent subject of the first photographers.34 Perhaps because of its stillness and brilliance. But beyond pragmatic and technical justifications, an essential kinship may exist that led photography, archeology, and sculpture to enter into this inextricable three-way relationship. The Patroclus by Fox Talbot (Fig. 8, see the text by R. Sachsse) has become an icon of early photography, and the idiosyncratic pioneer Hippolyte Bayard reproduced a series of antiquated statues and statuettes around 1840. Very often these were the plaster sculptures that populated artists’ studios. This is also the case in a photograph by Charles-David Winter around 1850 (Fig. 9): in the organized chaos of the studio, the "pencil of nature" illuminates numerous plaster sculptures, among them of course the Laocoon Group, the Apollo Belvedere, and the Borghese Gladiator.

The establishment of archeology as a specialist science accompanied the diversification and improvement of photo-technical practices taking place at breakneck speed throughout the mid-nineteenth century. The new medium, which was mainly seen as a technical achievement, replaced in a long-term process older, graphic-based representations in excavation reports and art-historical works. Behind this stood the optimism that prevailed from the outset—based on the possibility of reproduction liberated from individual handwriting and characteristic artistic style—to now possessing a previously unknown scientific objectivity, one particularly suitable for a material-fixated subject such as archeology.35 The fully automated genesis of imagery via the photographic machine, with more precise details than any drawing, was first and foremost understood as a scientific instrument. In this light, François Arago introduced the discovery of the daguerreotype before the Académie de Sciences in 1839. His text attests to the quasi-genetic relationship more than any photograph when, in reference to Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, he describes to his listeners what kind of unprecedented, documentary-scientific achievement would have been possible had the new technology already been available. "To copy the millions of hieroglyphics which cover even the exterior of the great monuments of Thebes, Memphis, Karnak, and others would require decades of time and legions of draughtsmen. By daguerreotype one person would suffice to accomplish this immense work successfully. Equip the Egyptian Institute with two or three [examples] of Daguerre’s apparatus, and before long on several of the large tablets of the celebrated work, which had its inception in the expedition to Egypt, innumerable hieroglyphics as they are in reality will replace those which now are invented or designed by approximation. These designs will excel the works of the most accomplished painters..."36 In the utterly exaggerated notion of a single photographer producing millions of daguerreotypes to capture the entirety of Egyptian antiquities lies the almost prophetic idea of what was to come; describing it here as the "flood of imagery," however, misses the mark, since it is too sudden. Early twentieth-century photography—not only digital imaging techniques—became archeology’s favorite adoptive child, which incidentally eradicated its "biological" parents and grandparents. This is because photography can reproduce anything the researcher finds informative regarding surface structure, from microscopy to material conditions, to traces of past human existence appearing on the earth’s surface in aerial photography.

Amin El Dib’s intimate view of plaster sculptures at the Skulpturhalle is therefore ultimately the view of an archaeologist, because he reveals with the camera structures where history is evident in multiple layers: the history of the plaster casts, the history of their originals, the history of archeology.

Wolfgang Filser, Berlin, February 2019

|

|

Fig. 1: Cast from a Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze original (Amazon type Sosikles, c. 430 BC). Replica cast after the lost original. Basel, sculpture hall

Fig. 2: Jean-Léon Gérôme, Michelangelo, 1849

Fig. 3: Plaster fragment from the left foot of Athena Velletri coming from Baiae

Fig. 4: Plaster fragment from Baiae from an after-cast of a bronze statue by the sculptors Kritios and Nesiotes (477/476 BC), inserted into a modern cast of a Roman-imperial copy (today Rome, conservator's palace)

Fig. 5: Antonio Canova, The three Graces, plaster model with measuring points for transfer into marble, Possagno,

Museo Canova, 1813

Fig. 6: Amin El Dib, from the series Body and Soul

Fig. 7: Photogrammetry of a torso in the Museo Barracco, Rome (W. Filser)

Fig. 8: Fox Talbot, Bust of Patroclus, 1844–1846

Fig. 9: Charles-David Winter, sculpture studio, around 1850

|

|

Image Credits

Fig. 1: Photograph collection of Winckelmann-Institut, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Fig. 2: Courtesy of Dahesh Museum of Art, New York, 1999.8.

Fig. 3: C. von Hees-Landwehr, Die antiken Gipsabgüsse aus Baiae. Griechische Bronzestatuen in Abgüssen Römischer Zeit (Berlin, 1985), plate 49c.

Fig. 4: C. von Hees-Landwehr, Die antiken Gipsabgüsse aus Baiae. Griechische Bronzestatuen in Abgüssen Römischer Zeit (Berlin 1985), plate 5.

Fig. 5: S. Ottorino, Antonio Canova. La Statuaria (Milano, 1999), Fig. 268.

Fig. 6: © Amin El Dib.

Fig. 7: © Wolfgang Filser.

Fig. 8: Public domain.

Fig. 9: Public domain.

Bibliography

von Amelunxen 1988

von Amelunxen, H. "Die aufgehobene Zeit." In Die Erfindung der Photographie durch William Henry Fox Talbot. Berlin, 1988.

Batchen 2010

Batchen, G. "An Almost Unlimited Variety. Photography and Sculpture in the Nineteenth Century." In Marcoci 2010: 20–26.

Billeter 1997

E. Billeter, Erika, ed. Skulptur im Licht der Fotografie. Von Bayard bis Mapplethorpe. Wabern-Bern, 1997.

Borbein 2000

Borbein, AH. "Zur Geschichte der Wertschätzung und Verwendung von Gipsabgüssen antiker Skulpturen (insbesondere in Deutschland und Berlin)." In Les moulages de sculptures antiques et l'histoire de l'archéologie, Actes du colloque international Paris, October 24, 1997. Edited by H. Lavagne, F. Queyrel, 29–43. Geneva, 2000.

Brinkmann 2001

Brinkmann, V. "Die Fotografie in der Archäologie. Historizität und Wissenschaftlichkeit

von Interessen und Methoden." In Posthumanistische Klassische Archäologie. Berlin February 19–21, 1999. Edited by S. Altekamp, M. R. Hofter, M. Krumme, 403–15. Munich, 2001.

Brinkmann 2013

Brinkmann, V., ed. Zurück zur Klassik. Ein neuer Blick auf das alte Griechenland. Eine Ausstellung der Liebighaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main, February 8 – May 26, 2013. Munich, 2013.

Cain 1995

Cain, H.-U. "Gipsabgüsse. Zur Geschichte ihrer Wertschätzung." In Realität und Bedeutung der Dinge im zeitlichen Wandel. Werkstoffe: ihre Gestaltung und ihre Funktion, Akten der interdisziplinären Tagung Nürnberg 6.-8.10.1993, Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums und Berichte aus dem Forschungsinstitut für Realienkunde, 1995: 200–15.

Dally 2017

Dally, O. "Zur Archäologie der Fotografie. Ein Beitrag zu Abbildungspraktiken der zweiten Hälfte des 19. und des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts." BWPr 143. Berlin, 2017.

Fendt 2012

A. Fendt, "Die Anfange der Berliner Gipsformerei in der Werkstatt von Christian Daniel Rauch und im Königlichen Museum." In Schröder, Winkler-Horaček 2012: 83–90.

Frederiksen, Marchand 2010

Frederiksen, R., Marchand E., eds., Plaster Casts. Making, Collecting and Displaying Classical Antiquity to the Present. Berlin, 2010.

Frizot 1992

Frizot, M. The "Parole" of Primitives. Hippolyte Bayard and French Calotypists, History of Photography 16, 1992: 358–70.

Frizot 1998

Frizot, M., ed. Neue Geschichte der Fotografie. Cologne, 1998.

Giuliani 2019

Giuliani, L. "Unser, Unser Winckelmann. Zwischen Kanonisierung und Verdrängung." Appearing soon in a conference edition Kunst und Freiheit. Eine Leitthese Winckelmanns und ihre Folgen, will be published by the Mainz Academy of Sciences and Literature.

Helfrich 2012

Helfrich, M. "Die Gipsformerei of the Berlin Museums." In Schröder, Winkler-Horaček 2012: 81– 82.

Holm 2012

Holm, C. "Goethes Gipse. Präsentations- und Betrachtungsweisen von Antikenabgüssen im Weimarer Wohnhaus." In Gipsabgüsse und antike Skulpturen. Präsentation und Kontext. Edited by C. Schreiter, 117–134. Berlin, 2012.

Kader 2000,

I. Kader, "Gipsabgüsse und die Farbe Weiss." In Les moulages de sculptures antiques et l'histoire de l'archéologie, Actes du colloque international, Paris, 24.10.1997. Edited by H. Lavagne, F. Queyrel, 121–55. Geneva, 2000.

Klamm 2017

Klamm, S. Bilder des Vergangenen Visualisierung in der Archäologie im 19. Jahrhundert – Fotografie, Zeichnung und Abguss. Berlin, 2017.

Landwehr 1985

von Landwehr, C. Die antiken Gipsabgüsse aus Baiae. Griechische Bronzestatuen in Abgüssen Römischer Zeit. Berlin, 1985.

Landwehr 2010

Landwehr, C. "The Baiae Casts and the Uniqueness of Roman Copies," in Frederiksen-Marchand 2010: 35–46.

Lochmann 1988

Lochmann, T. "100 Jahre Skulpturhalle Basel (1887–1987)." In Kanon. Festschrift Ernst Berger zum 60. Geburtstag am 26. Februar 1988 gewidmet, ed. M. Schmidt, 370–76. Basel, 1988.

Lochmann 1995

Lochmann, T. Sehnsucht Antike. Johann Rudolf Burckhardt und die Anfänge der Basler Abgussammlung. Ergänzungsschrift zur Sonderausstellung in der Skulpturenhalle Basel, 17. November 1995 bis 28. April 1996. Basel, 1995.

Lyons et al. 2005

Lyons, C.L., Papadopoulos, J.K., Stewart, L.S., eds. Antiquity and Photography. Early Views of Ancient Mediterranean Sites. Farnborough, 2005.

Malvern 2010

Malvren, S. "Outside In: the After-life of the Plaster Cast in Contemporary Culture." In Frederiksen-Marchand 2010: 351–58.

Marchand 2010

Marchand, E. "Plaster and Plaster Casts in Renaissance Italy." In Frederiksen-Marchand 2010: 49-79.

Marcocci 2010

Marcoci, R., ed. The Original Copy. Photography of Sculpture. 1839 to Today. New York, 2010.

Myssok 2010

Myssok, J. "Modem Sculpture in the Making: Antonio Canova and plaster casts." In Frederiksen, Marchand 2010: 269–88.

Savoy 2003

Savoy, B. Patrimoine annexé. Les biens culturels saisis par la France in Allemagne autour de 1800, vol. 1, 14-49. Paris, 2003.

Schreiter 2010

Schreiter, C. "’Molded from the best originals of Rome’ – Eighteenth-Century Production and Trade of Plaster Casts after Antique Sculpture in Germany." In Frederiksen, Marchand 2010: 121–42.

Scheiter 2014

Schreiter, C. Antike um jeden Preis. Berlin, 2014.

Schröder, Winkler-Horaček 2012

Schröder, N., Winkler-Horaček, L. ... von gestern bis morgen … Zur Geschichte der Berliner Gipsabguss-Sammlung(en). Rahden, 2012.

Shanks 1997

Shanks, M. "Photography and Archeology." In The Cultural Life of Images. Visual Representation in Archeology. Edited by B.L. Molyneaux, 74–107. London, 1997.

Socha 2015

Socha, S. "Der Antikensaal." In Tempel der Kunst. Die Geburt des öffentlichen Museums in Deutschland 1701–1815. Edited by B. Savoy, 385–412. Cologne-Weimar-Vienna, 2015.

Sünderhauf 2004

Sünderhauf, E. S. Griechensehnsucht und Kulturkritik. Die deutsche Rezeption von Winckelmanns Antikenideal 1840–1945. Berlin, 2004.

Vitti 2016

Vitti, P. "Survey of Historical Heritage in the Era of Computers: A Matter of Aims and Methodology." In ΑΡΧΙΤΕΚΤΩΝ. Honorary Volume for Professor Manolis Korres, 693–98. Athens, 2016.

Wittkower 1977

Wittkower, R. Sculpture. Process and Principles. London, 1977.

|

|

|