|

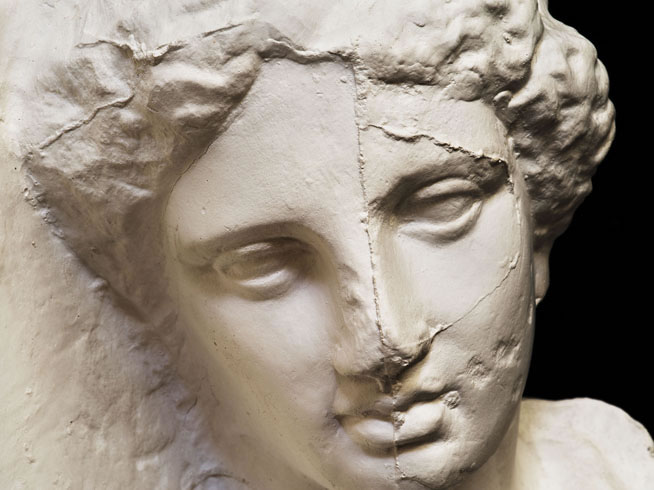

A comparatively small visibly undersized head, seen in the image from above at an oblique angle against a black background, also tilting to the left; a serene, introspective, evenly proportioned face with full lips, a straight nose, and thick eyelids under a uniform, not entirely symmetrical fringe of hair. Visible on the left, close to the head, an irregularly structured but nearly flat surface, out of which the head appears to grow. The image depicts a cast replica of a marble sculpture of a mourner on a headstone from the fourth century BC, likely cast at the end of the nineteenth century. The beautiful and smooth face shows traces of destruction and reconstruction: a trapezoid rectangle formed with the right eye appears to have been removed from the sculpture, reconstructed, and re-inserted; broken edges are also visible directly underneath the hairline and above the center of the chin. Indications that the section was reassembled—potentially a modern modification—have not been erased; they stretch like scars in the plaster across the otherwise smooth surface of the soft material. Even if the image depicts a white sculpture against a black background, delicate browns, yellows, and blues shimmer through in the sections in shadow.

Over a three-year period, Amin El Dib took photographs inside Skulpturhalle Basel, where cast plaster replicas of antique sculptures are housed for study purposes. That these are hardly studied anymore threatens the collection in its current presentational format with closure or downsizing. Was it this cultural, political fate, the fact that the photographer could cleverly span waiting times at the nearby university hospital, or a general interest that inspired him to create a photo series of the plaster casts? Regardless, both the concept and execution suit his body of work well. His long-term projects in particular, from Inszenierte Bildnisse (Staged Portraits) to Bilder von Menschen und Tieren (Pictures of Men and Animals), to the Weekenders and Under Skies of Blue and Gray, are repeatedly incorporated as references or assert themselves in one way or another throughout the images and their interrelationships. Conversely, in this series of still lifes, Amin El Dib experiments with new forms that radically expand his body of work, specifically in terms of color, clarity, and other photographic parameters.

In a photo of several sculptures and groups of figures, a larger-than-life-size Menelaus stands out; it appears just to the left of center in the image, holding up the lifeless body of Patroclus. To the right is a model of the Parthenon on a pedestal of rectangular panels. On the far right and far left are two sculptures as well as two columns, one of these is part of the architecture; the other is also a plaster cast. Menelaus’s prominent helmet overlaps the edge of a skylight, the arrow of an illuminated emergency exit sign points at the nose; a tall ladder is positioned behind the group of figures, the tops of which protrude out of the image. The entire space reads visually as half a room; a highly polished stone floor fills the lower third of the image, a wastepaper basket and a toolbox on wheels are seen near the left edge. Except for a recess on the left sculpture filled with artificial light, the image is illuminated by the room’s muted skylight. Depicted is a typical setting of an exhibition being set-up.

“How One Should Photograph Sculptures” is the title of an 1896 essay by art historian Heinrich Wölfflin. This topic was so important to him that he republished a revised version in 1915.1 Most of his guidance came from Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, a German photochemist who gave numerous talks on the subject. But the two basic instructions these authors offered—to always position light-colored sculptures against a dark background and to photograph these with indirect light—were borrowed from the oldest photo book ever: William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature from 1844.2 To illustrate his ideas, Talbot used a plaster-cast bust of Patroclus, positioned in a black-fabric lined niche at his home of Lacock Abbey. This topic was also so important to him that he presented a second plate of this bust in the book—the text describes the importance of selecting the proper angle for all objects, since in his view this was the genuine difference between “photogenic drawing” (i.e. photography, which was not yet known as such) vs. drawing with pencil. This is precisely where the work of Amin El Dib begins, in the selection of the horizon, in the proximity to or distance from the objects, and at some point also in the choice of detail, with and without the surrounding space.

Once again an image of what is called the “Pasquino group,” with Menelaos and a deceased Patroclus, this time in a completely different composition and perspective. A voluminous body part forms the left half of the image—only those familiar with the entire group of figures recognizes this as the shoulder and upper left arm of the deceased Patroclus. A face fills the right side; shown upside down, it is theatrically illuminated like a mask from below by the sculpture hall’s skylights. The view of the group in the room with the model of the Parthenon presents the dead figure as a headless torso; the head here becomes the element of a physicality that is only briefly insinuated but portrayed vitally overall. Also contributing to this are the incisions of reconstructive efforts on the arm and shoulder, which cut across the lower quarter of the image in the form of faint but distinct black lines. Where the sculpture reflects itself, between the head and the body, the plaster appears rather yellowish, otherwise it is reflected, apparently painted in earlier times, in minimal nuances of gray to red. At no point can the entire group of figures be inferred from the picture.

Playing with perspective in close-up is a characteristic of classical modernism in photography. From Paul Strand’s fenders, coffee tables, and typewriter keys to the close-cropped portraits of László Moholy-Nagy, to the Moscow architecture of Aleksander Rodchenko, photography of the 1920s moved purposely away from the composed image toward a discussion of composition as the image, whether referred to as “straight photography” in the US or as Neues Sehen in Germany.3 The long-term preoccupation with this imagery runs throughout Amin El Dib’s entire body of work, and his last series already provided a clear sense of how critically he views the harsh parameters of this visual program, in particular at the end of analog black-and-white photography.

The Aphrodite of Melos stands, white on a black pedestal, in front of sections of the Parthenon’s south frieze, positioned in two rows before the wall on mounting plates. The version of the mother of all plaster replicas seen here has been modified, the added-on tip of the nose and anterior part of the left foot are hardly recognizable. Viewed from approximately waist-height in the room, the freestanding figure looks oddly diminutive in front of the huge reliefs of charioteers and groups of horses. The yellowish reliefs also provide a cold-warm contrast: Aphrodite seems almost blue in the complementary contrast to the reliefs; this is also unaffected by lighting fixtures visible in the image. The slightly angled view of the exhibition hall’s rear wall makes the room appear sealed-off, nothing remains of the celebration of beauty in the countless views of Aphrodite against a dark background—it is up to the view to free up the figure portrayed, returning to it the volume that is anchored as a tourist image in the minds of many.

As Hélène Pinet noted in her very first essay on the photographs of sculptor Auguste Rodin, marble and plaster in particular were preferred to bronze and wax when it came to capturing the master among his works.4 This was not only because the film and plates of the period around 1900 failed to accurately record reds—all red tones appeared darker than when viewed in person—but all images created photographically were monochrome and not at all purely black and white. Thus, early twentieth-century maps and atlases, with their depictions of sculptural works of art from antiquity to the High Middle Ages, also required on principle that every work of art be presented individually against a neutral ground, in some instances as a light-gray object against a dark gray or black background, in others as a medium-gray object against a lighter, but never purely white ground.5 The practice of plaster casting and monochrome photography were mutually dependent: what could be more easily photographed was deemed more beautiful. Amin El Dib explores this in depth in his Basel series, also in terms of his use of digital color photography.

Fourteen sculptures of various epochs in a single image, often only small parts of which are visible and overlapping in multiple forms; except for two figures none is recognizable in its entirety. The background is dark, almost black, the floor narrowly cropped out; the pedestals have no relationship to the ground and therefore also no effect on the perspective of the image. The soft light from the skylight illuminates all figures so uniformly that no hierarchy or meaningful order results. Thus, the eye is able to concentrate on juxtaposed individual gestures and forms with no relationship to one another: the raised hand of Hera on the left—originally named Hestia Giustiniani after the location where it was found—stands in the room as solitary as the frenzied twisting of a fleeing Nereid on a fish on the right edge of the photograph. The only differentiating element of the arbitrary grouping is the coloration of the figures. It ranges from a cool white gray of the two outer figures to the yellow of the Nereid, to the orange of the rear figure right of center in the picture; colors indicate the different casting processes of each plaster figure and their preservation with monochrome paints. The overall image composition might recall people waiting in line at a bus stop, also and precisely because of the narrow strip of blue and red color areas on the upper edge of the photo recalling billboard surfaces. Such associations have their reasons: ultimately the Greek and Roman deities featured here are part of an extensive narrative that is, however, not (yet) recognizable in this image.6

The history of the collection of antique sculpture plaster casts is one of a medium and thus follows a dynamic that Amin El Dib repeats in a similar way for his medium of photography: already a familiar practice in ancient times, the plaster cast in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries became one of the most sought-after media in both art and scientific education as well as a focus of the bourgeoisie’s passion for collecting. Greater use of industrialized production methods brought costs down, which also made cast sculptures available to a larger segment of the population.7 The museum movement of the nineteenth century integrated plaster cast collections according to their educational purposes. Up to the 1920s, this fomented not only heated debates on specific questions of how to present, preserve, and use these sculpture replicas but even ideological battles around the question of coloration or the untainted appearance of fresh plaster, which, however, tends to attract dust more rapidly, and this in more than one respect. Classical modernism of the mid-twentieth century, with its myth of the original, sought to do away with all plaster casts, and only the post-modern repurposing of casts via art’s conceptual strategies, as well as newer definitions of the responsibilities of museum presentation, have at least created for plaster cast collections a small, albeit not entirely safe niche existence.

A lean torso of a slender, obviously very youthful figure cuts across the center of the horizontal image, cropped off below at the knee, at top just above the hip skirt. The figure is bent slightly forward, the right arm somewhat drawn back, on the angled left arm only the hand is visible. The hands can be interpreted as later additions to the sculpture; their splayed fingers do not match the Greek athlete from the fifth century BC, whose Roman replica survived as a marble statue without arms and nose. The exacting photograph captures the statue in sidelight and slightly illuminated from behind, likely the way it corresponds to its positioning inside the sculpture hall. Visible in the background are out of focus text-panels with white letters on a varying red background; the image presents not only the sculpture but its function as an exhibition piece in a context obviously requiring more extensive clarification.

The research of Jakob Ignaz Hittorf and Gottfried Semper into the coloration of ancient temples, along with their statues, may have been a horror for the classicalist aesthetes of the early nineteenth century trained in Winckelmann, Schiller, and Goethe. The color plates published were far too colorful; the notion that walls, columns, sculptures, and reliefs had color was too shocking.8 In terms of medium, early photography and the plaster cast remained close for nearly a century; not until digitization was the barrier finally lifted to perceiving color as the guarantor of visual media’s proximity to reality. For Amin El Dib, this question has taken on increasing importance in the course of his work at Basel Skulpturhalle and his images address this on two levels: on the one hand, chromatic differences in monochrome paints or pure plaster sculptures serve as the thematic focus in numerous cases, for instance, in the photo of Demeter of Knisos in the variations between Three torsos with their cold-warm contrasts, or the head of Cleopatra with her two secondary figures and the red wall in the center of the picture. On the other hand, however, the photographer uses such minimal coloration this conveys the impression that the images are black and white, for example in the two images of Aphrodite from Este and Hera-Borghese from Baiae. And, thirdly, the photographer—as evidenced not only in the image of the female athlete but also in the dancing Maenad, the so-called Berlin dancer—brings to the image the discussion of coloration elsewhere as anticipated in any perceptual expectations: the background fundamentally affects our perceptions and alters the color of the object more powerfully than we are willing to consciously acknowledge. More than ever before in photography, this is a hallmark of the digitization of the medium.

A close-up of a seated man with a thin cloth draped over his body around the waist, falling on his thighs in narrow folds. The right arm of the figure can be made out on the left side of the image, but is barely recognizable as a result of damage. The left hand, also severely damaged, extends past the folds, and shows the traces of an impact on the back of the hand and chipping on the visible three fingers. Given the sculpture’s condition, one must conclude that the hand’s thumb and index finger have been broken off, but it might also be that these are simply not visible from the perspective the image presents. The plaster was evidently painted a shade of yellow, and the damage might well have happened later, but still be so long along itself that determining this accurately is no longer possible. In contrast to the close-up of the deceased Patroclus, this photograph depicts a listless body with an equally listless hand; the damage underscores this lifeless state. The picture shows a close-up of a Roman replica of a statue of Epicurus seated, which has been modified numerous times over the past two centuries and furnished with various heads.

Paul Zanker, in his wonderful and wondrous book on the image of the intellectual in Greek antiquity, draws attention to the depiction of the undignified, listless bodies of aging philosophers, which reinforces even more the luminosity of the philosophy they represent.9 Amin El Dib references this representation by visualizing the destruction of ancient thought, as demonstrated in new philosophy and, above all else, in media theory, in the damage to the sculpture. What photography cannot illustrate visually is when the damage occurred: in antiquity, during one of the many modifications to the overall sculpture between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, or simply to the replica exhibited in Basel, in the form of an accident or careless handling of the plaster cast as a worthless reproduction. Even more so than its analog predecessors, the color digital image is uncoupled from the veracity of its reference to reality: a savvy digital image processing specialist can easily create with the computer the same kind of depictions of damages the photographer has carefully reproduced on site.

An oval surface as the blank shape of a head, highly structured by strong lighting from the right, ringed above and on the right by a fringe of hair, beneath which two wide-open eyes are visible. Near the bottom is the torso of a male neck, whose smooth surface provides a contrast to the roughness of the main surface essential to the image. When the large-scale frieze on the east side of the Pergamon alter was created, the face of a young giant, struck down with a bolt of lightning by Zeus standing over him, was located here. Whether this face was already lost in antiquity or during the reasonably challenging excavation of the entire altar at the end of the nineteenth century cannot be determined. The careful flatness of the broken-off face suggests an arbitrary act, since all details of the fringe of hair and eyes are almost completely preserved. Unusual for this image series, the potential violence of this supposed act of removing or breaking off of a face is amplified again by the intense side lighting—but determining any of this is impossible while observing the picture.

A casual, first consideration of the photo series upon reading the title Von der Brüchigkeit des Seins (On the Fragility of Being) may give the impression that Amin El Dib was only concerned with the damage to the plaster casts; all too obvious are the pits, cracks, broken spots and edges, and additions. But the photographer is not interested in creating “depictions of damage” as a kind of instructional model for conservators, but rather—as the title also quite wrily suggests - in the concept of beauty generally and its fragility, which can certainly serve as a clarification of existing aesthetics: during the Second World War, certain municipal politicians or monument conservators not only recommended that destroyed properties around the city be photographed in their entirety, primarily so that the design intents of earlier architects be more easily clarified visually than the state of their completed works, but this gave rise to an entire genre of documentary photography after the war.10 But these kinds of cultural, historical arguments are not part of Amin El Dib’s imagery; many works are too reminiscent of earlier series for this: the muscular torso of a fallen soldier, a broken-off arm before a female body, or a thigh against a blue background, displaying cut and cracked surfaces in each case, are reminiscent of the many enormously vital but often also fragile figures of the photographer’s earlier series. The abstract surface of the Belvedere Torso’s front side evokes the Weekenders series, and even more so the beautifully titled series SilberLicht (Silver Light) in which the surface of the photographic material plays the central role.11 Digital photography and its specific coloration, was also evident in several of his series and groups of works before employing it at Basel Skulpturhalle. He even repeatedly tried grouping individual images together—diptychs and triptychs are present throughout his entire body of work; he could even finish this group of works with a triptych of images from the ground floor of the hall.

A concise bust of a handsome youth. The head is brightly illuminated from the left, allowing the head’s left half to recede completely into the darkness of the shadows. The same shadow falls at an oblique angle onto the left shoulder of the upper body. The coloration of the plaster cast of a youthful figure—interpretations range from Discophoros of Polyklet to a Roman statue of Hermes—is a whitish yellow; apart from several surface scratches, the upper body and face are immaculate. The hairline above the truncated forehead is oddly indistinct, and a good third of the cranium is simply cut away, as if sliced or sawed off, the imperfection forming a nearly circular disk. Brightly illuminated and at an oblique angle, it contrasts with the opposing slant of a black wall in the background and an overhead skylight, which appears as a blue triangle in the left half of the image and forms a white to light-gray column shape on the right edge. The complementary contrast between the yellow plaster—possibly from sunlight—and the pastel shades of the blue background is situated directly against the hard black shadows and the nearly white missing surface of the head.

Amin El Dib’s portrait bust of the young man in plaster has a contemporary parallel: in 2014, a monographic exhibition by US sculptor Charles Ray was shown in Basel, and the sculpture used for most press images was a larger-than-life boy holding a frog. Its white painted surface—the sculpture is actually made of steel and plastic—directly recalls the plaster casts; it was also presented in front of a pale blue sky. With this image, Amin El Dib has thus arrived in this series at the forefront of all debates regarding the visual art of his time: with the plaster cast it is no longer possible to determine what the original version of the sculpture was—whether marble or bronze, painted or unpainted. Even the surface, for all intents and purposes an essential guarantor of the reference to reality in all photographs, does not give anything away in Amin El Dib’s image: the imperfections draw attention to the plaster captured by the photographer, nothing more; the bronze or marble version might also indicate a similar depiction of damage, but surely this is not all. And again: an experienced practitioner of digital image processing could quickly add any of the imperfections seen here to the image itself but not to the original that has been photographed.

It is therefore necessary to differentiate between the depiction of damage and the torso, and do so in an entirely postmodern way that goes beyond the sculptural category of intentional incompleteness and a reductionism that is acquired over time.12 The sole meaning of the phrase torsi addito tempore is that no state is stable, everything is in constant flux—and only photography can detach the image from time; this is its fascination, in Lessing’s words, “its transitory moment.”13 However, the increasingly tenuous connection between image and the reality it seeks to portray is also a central theme of the artist Amin El Dib in working with the medium of photography. Context and communication first create the work, this wisdom has from the very beginning consistently inspired the former architect and his work as an artist in reflecting on photography. Throughout this text and the descriptions of his images, color and form are discussed more frequently—but solidity is the constant factor in the images that convey the medial conditions of their perceptions: the forms are solid, the colors are fragile, and the surfaces are recognizable as solid bodies only through the depictions of damage. Extreme close-ups—always a characteristic feature of Amin El Dib’s photography—focus attention on the question: which surface perceptions can still be trusted at all? All forms, however, are always vital, not humanized, but derived from human perceiving.

More than a decade ago, Susanne Regener noted the degree to which digitization has changed our view of the past.14 Amin El Dib has been witness to such changes on many levels via his own personal history. For him, the encounter with the replicas from antiquity and the questioning of their originality stemming from this, and thus their cultural-historical value—from which only an art about art can arise—also has another frame of reference. But he only finds the most important pieces representing half of his cultural heritage in those museums that can only be designated with great difficulty as the guardians of colonialist-seized treasure—thus stripped from the peoples who own them —of human knowledge, culture, and art. Through his eyes, the solidity he gives the damaged bodies and sculptures also signifies a personal affirmation of his existence in photographic works, not in the sense of an Instagram photographic selfie, but in the attestation of cultural damage caused by migration, multiplication, and reproduction. For him, depictions of damage are thus testaments to his perceptions and processes as a visual artist, the synthesis of his migrations through the history of his medium, his artistic impressions, his view. The fact that beautiful images and excellent works result from all this should bring delight to anyone apprehending these narratives visually.

Rolf Sachsse, 2019

|

|

----------------------

1 Heinrich Wölfflin, “Wie man Skulpturen aufnehmen soll,” in Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst (Leipzig) NF7.1896.224-228; NF8.1897.294-297; NF26.1915.237-244.

2 William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature (London, 1844), Plate V and Plate XVII; quoted in Die Wahrheit der Photographie, ed. W. Wiegand (Frankfurt, 1981), 64, 79.

3 Van Deren Coke, Avantgarde Fotografie in Deutschland 1919-1939 (Munich, 1982).

4 Hélène Pinet, “Les photographes de Rodin,” in Photographies, Recherches Historiques et Critiques (Paris) 1.1983.2.38-58.

5 Rolf Sachsse, “Bilderblock und Tafelteil. Zum Verhältnis von Bild und Text in kunstwissenschaftlichen Großpublikationen vor 1933,” in Atlanten des Wissens. Adolph Goldschmidts Corpuswerke 1914 bis heute, eds. Kai Kappel, Claudia Rückert, Stefan Trinks (Berlin, Munich 2016), 32-43.

6 See Bernhard Mensch, edited by Peter Pachnike, exh. cat. (Götter, Helden + Idole: Oberhausen, 1998).

7 Frank Matthias Kammel, “Der Gipsabguss. Vom Medium der ästhetischen Norm zur toten Konserve der Kunstgeschichte,” in Ästhetische Probleme der Plastik im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, ed. Andrea M. Kluxen (Nürnberg, 2001), 47-72. As well as the following comments from this text.

8 Gottfried Semper, “Vorläufige Bemerkungen über bemalte Architektur und Plastik bei den Alten (1834),” in Kunsttheorie und Kunstgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts in Deutschland, vol. 2 Architektur, Texte und Dokumente, ed. Harold Hammer-Schenk (Stuttgart, 1985), 95-100.

9 Paul Zanker, Die Maske des Sokrates, Das Bild des Intellektuellen in der antiken Kunst (Munich, 1995).

10 Ludger Derenthal, Bilder der Trümmer- und Aufbaujahre. Fotografie im sich teilenden Deutschland, PhD dissertation 1995 (Marburg, 1999), 44-86.

11 Amin El Dib, SilberLicht (Berlin, 2007).

12 Wolfgang Brückle, Kathrin Elvers-Švamberk, Von Rodin bis Baselitz: der Torso in der Skulptur der Moderne, exh. cat. (Ostfildern-Ruit, 2001).

13 Handwritten notes by Lucia und László Moholy-Nagy during preparations of raum 1 for the exhibition Film und Foto 1929 in Stuttgart, Estate of Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin.

14 Susanne Regener, “Bilder | Geschichte. Theoretische Überlegungen zur Visuellen Kultur,” in Die DDR im Bild, Zum Gebrauch der Fotografie im anderen deutschen Staat, eds. Karin Hartewig, Alf Lüdtke (Göttingen, 2004), 13-26.

|